Great people make the great teams that make the great workplaces, and Mr. Asmat Yousri is a big believer in people. After all, he has been at this since 1996. An ex-banker, he saw no obstacles transitioning from a corporate position to an entrepreneur. In fact, the former has helped him understand the value of process and how to use it to enhance his own business.

A fascinating interview, Mr. Asmat is one of those rare people able to balance deep thinking with practicality.

Enjoy.

Genup: Please tell us about yourself.

Asmat: Born, raised largely in the United States, except for a small period in the Middle East in Egypt. Education was in a British school, then purely in the United States. University, both undergraduate and postgraduate, undergraduate was Political Science, Foreign Affairs. Graduate was International Economics. An additional year in France doing again International Economics in the South of France.

So combination of languages and a lot of intellectual curiosity and helpful connections, mainly my father.

First job was with a steel company, Ammco Steel, specialty steel company back when steel was big in the United States. Started out in Ohio, which was the home of this particular company. Then they moved me to Paris, then they moved me to Sub-Sahara Africa; Kinsasha, Zaire back when it was Zaire. Back to Middletown, Ohio. Left steel and went into banking on a whim. In other words, my sister was a banker at the time with Chase. She said, “Given your analytical skills and your ability to communicate in the English language, why don’t you do give banking a try?” So I did.

I knew a couple of people in banks; Manufacturers Hanover, but the one that I landed with was Mellon Bank. So Mellon regional bank based in Pittsburgh belonged to the Mellon family. That basically was the wealth behind Pittsburgh Gulf oil, US Steel, Westinghouse. Some pretty big companies that they were behind, and Mellon was the bank equivalent at the time to JPMorgan, not Morgan Stanley. JPMorgan was the bank. With that, we went to Hong Kong, New York, because there was no cross border or interstate banking.

All of my languages were European. So of course, the bank sends you to Asia, so Japan, Taiwan and from Taiwan, servicing basically the region. Went to Milan, handled Milan and Greece, back to Pittsburgh, left banking. I always said as bankers, we always believe that we know numbers, we know how to rip apart a financial statement, we know where things hide, what typical ratios are like. We got to know our industries pretty well and the numbers talk to us. We always felt empowered as if, if we see the numbers, we can decide on the solution.

Not so.

The first company that I started of any substance, I thought because of my Thai wife, to straddle the West and Thailand. Thailand; easy entry economy is, it doesn’t take a lot to get started. It’s not zero, because we built a factory. We did everything by the book. So we have chart of accounts, process. Everything was the way we were taught. The thing that we lacked were basically clients. We manufactured stuff, but no clients, because we were a little bit light on the business development side. By the time that caught up, we had moved from golf to rubber products for sports shoes.

Lucky, we had captive clients, and Thailand at that particular time was big in sports shoes still. So we dealt with all of the large ones; Nike, Adidas, New Balance and they were all clients.

Fortunately, we didn’t have to export. We would sell to the manufacturers of the shoes themselves.

So we had the outer soles, we had various component parts. Then the shoe industry was impacted.

Genup: Which year was this about?

Asmat: This is about 1996, 1997. By 1997 after we sold, deciding, “Okay, what now? Go back to the States, hang out in Thailand and do nothing.” That’s not very appealing. With two relatives, ABC, American-born Chinese, one in Hong Kong in trading with his in-laws, another one back home in New York working for AIG as the head of their technology, we decided, “Let’s do something with computers, because we had been using computers since, gosh, the 1970s. The late 1970s when you did a spreadsheet at the bank, you inputted yourself, you did the ratios yourself, you had dumb terminals that were connected to a mainframe.

We were pretty comfortable with computing, so we said, “Okay, it’s the next new thing. Let’s do something with computers, and web was getting big. So we said, “Well, what makes sense is have a place for web development to reside.” So hosting, and hosting was easy entry, no big people in hosting. We went out, we got clients in Hong Kong, in the United States, even in Thailand, but something really odd was happening. Most of the people that wanted a web presence and believed that this is the new way to do business is they wanted somebody to develop it for them.

So hosting died as money poured into the hardware, software business, what ultimately became a dev ops business. We were pushed into development, which was largely visual impact and a little bit of tech in the background. Mostly graphic and graphic design. Our first team was heavy duty creative graphic, and we taught them how to do HTML and coding. As we grew, we realized that we didn’t need clients, because clients found us because we were one of very few developers and there were no developers in Thailand at the time. So we had more than enough business, and we were dealing with financial institutions, and I was very comfortable talking to large companies. All of a sudden, we’re competing with agencies; O&M, Grey, McCann, and we don’t have the name. We have the capability.

So what happened is the agency became the front end and we became the factory. There’s not a lot of money in being a factory for an agency. They pitched the concept to the client. Even though we would pitch the concept to somebody like O&M with whom we still deal is they basically had the people and the stature to sell it to the client. We got squeezed. At early 2000, we were thinking, “Gosh, we’re in a new media business. We should be thinking about next steps.” What other people were doing was, they’re dropping the web business and going straight into the coding business, the application development, which were resident on the web. But they got away from the pretty pictures.

Our name was made, because our designs were great.

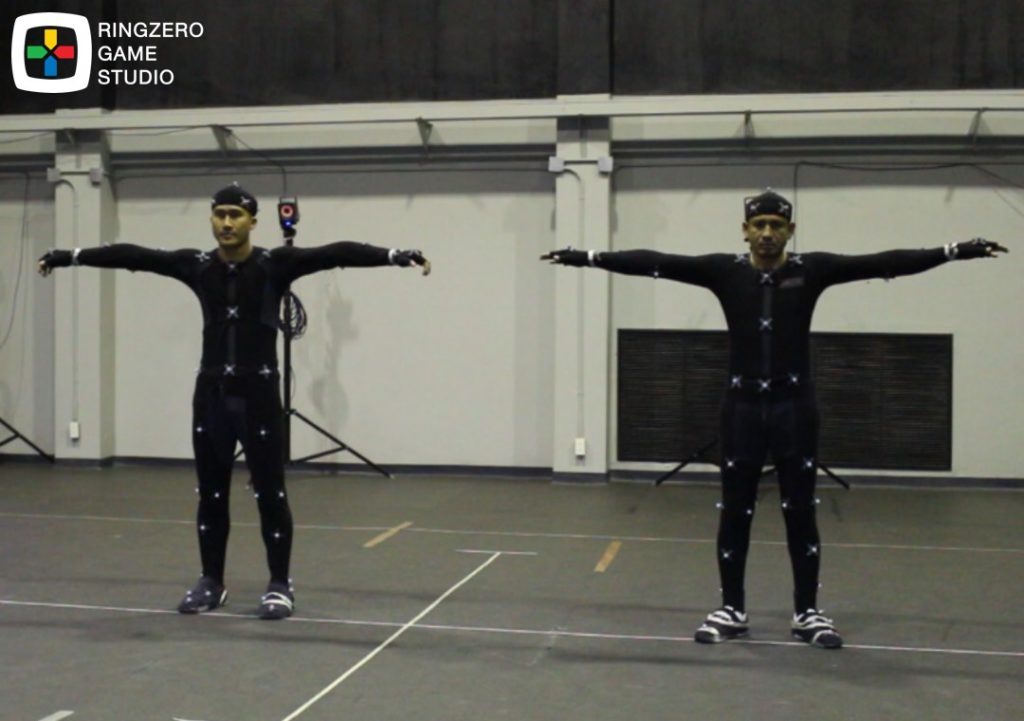

Genup: Was it the same name, RingZero at that time ?

Asmat: Yeah, exactly. We started as RingZero. RingZero means in software architecture, the most trusted core is known as Ring-Zero and then it moves out in concentric circles, Ring 1, Ring 2, et cetera. We went with RingZero. It was technically an interesting name, so it stuck, and we still have it. Not that anybody associates us with anything in particular, but it was the tech guy in New York that basically gave us the name.

Okay. Here we are. We had just suffered through basically the end of dot com, so the 2000, the turn of the century.

Thinking heads basically said, “Wait a second, business is business. It doesn’t matter where you do it. So let’s stop, think about how we’re going to use this new medium and treat it like a real live business.” For 2000, there was no business. So we built up our team, we built up our capabilities, we kept talking to clients that were with us, the financial institutions and we began thinking, “Okay, let’s get bigger.” We had the first acquisition, somebody that was impacted by the dot com collapse, decided they’re going to go back to the UK. We said, “We like the people that you have. We like the clients that you have. We’ll buy you.”

Bad idea. In technology, you’re only as good as your people. It’s the people that make the company. In doing the transaction, we didn’t protect ourselves. We didn’t say, “You need to guarantee at least a year of the full team that we acquired.” At the end, we had something like four or five people left, some that couldn’t go elsewhere, but one that felt at home, because I was an American, he was an American. He was a Stanford grad, UC Berkeley-

He became my first general manager.

At that time, I started thinking about, “Okay, so new media, what are we going to do with this thing? I’d like to find some use for the assets that we have,” but it kept on chugging along. We kept on having enough clients to feed us. But in 2003, we decided, “Okay, in addition to the new media business, let’s get into real development.” So we hired somebody that had been with an Indian company that basically were at the forefront of professional services. He was with one of the bigger companies and he brought clients, he brought resource list; basically, a one man department by itself.

MJ, that was his name, built up our professional services.

So it really took off. We had at one time 80% of all the COBOL developers in Thailand that were in professional services. We had Java people, until another company came in and hired all the Java people it seems in Bangkok and overpaid them. Then you couldn’t find Java to save your life. So we went into C#, and since that time, we’ve been a Microsoft partner. In 2004, we got pretty big and I started thinking, “Maybe this is a time to think about an exit. Bring in a heavy-duty partner.” To grow bigger, we started looking at all the acquisitions that we didn’t make.

We found one that had already been acquired by an Australian company, and it’s a listed Australian company. We said, “Okay… let’s merge with them and do a backdoor listing where they would in fact list the local company.” Well, we taught them how to do professional services. Our new media effort was really good. These guys were sharp on business development. Well, you know what, never enter into an arrangement until all of the contracts and paperwork is completely done. So it wasn’t. The CEO in Australia changed. The new CEO decided he didn’t want to be partners with RingZero.

We took them to court. We lost.

We continued, and in 2005, we basically were shrunk, and we now have created a competitor in professional services. It was a listed Australian company. We had left some of our people behind. Nevertheless, we had two efforts; new media and what we called the creative group and professional services. Professional services went straight up. It was the right time to do professional services.

Genup: When you say professional services, you mean –

Asmat: Outsourcing. At the same time, companies like TCS were just getting started.

MJ basically grew up in this business, and he was very, very good at networking. But unfortunately, he had left us pre-merger and turned up later as our competitor with a company called NES that still exists. He was a partner in NES that had more than one office. We had lots of competition, but we still got to be fairly big. We still had about a hundred people. For a small company, that was pretty impressive. But the real issue is, what do you do with that?

I had already begun to start to think about games by 2006.

While the IT business was growing and funding us to move forward, we added work for hire. Work for hire, basically is you do the development of an application that was basically based on the web. We got involved in things like AOL, which was a competitor. Not American Online. AOL was a travel booking site. It started at exactly the same time as Agoda, and in fact competed with Agoda. We were the ones that developed it.

The people behind that was the owner of Asian Trails. Asian Trails is big travel agency, the guy, Luzi Matzig that started Asian Trails came out of Diethelm Travel. So Diethelm Travel was the mother of all travel agencies in Thailand. Luzi knew a colleague that was working with us at RingZero. Diethelm was still growing, still big, but Diethelm Travel was competing with people like Asian Trails. Here we are, developer, and right next door to us is AOL run by a person that works for Luzi to create this booking portal, and exactly the same formula as Agoda. But for some reason, Luzi decided to scrap it, and sold Asian Trails, for something like $150 million, and essentially continued to run the company as chairman, but now all his pet project, payment gateway, that we were working on as well, as well as the booking, it basically got scrapped. Nevertheless, so work for hire. We worked on some pretty interesting projects. What we realized is in the services business, you are vulnerable particularly to your own employees. Unless you locked your employees in, in some fashion, very, very likely you are creating your competition.

If you remember MJ that basically started professional services, he went on to compete with RingZero. The company that we had merged with went on to compete with RingZero. Thirdly, the person that I got to run the professional services area went on to create another company and competed with RingZero. My ex-director also indirectly competed with RingZero.

So focusing on professional services and work for hire, we were looking for ethical standards, somebody that abided by the law. We hired a Thai and pretty much taught him how to do professional services. He supposedly came from a project management background. Big company, but they didn’t do very much in Thailand. We brought him in. He did a pretty good job, because I married him off to a senior Thai that was very, very good at business development. I had a tech guy, a business development guy. They really did very well.

What happened is the guy that we brought in to run it started his own company. All these people still continue to exist with these companies. The person that was with us that was a senior Thai, he’s the only person that didn’t do that.

On the IT side, I’m thinking, “Okay, something is wrong with this formula,” but we still continued to limp along on the IT side. Finally, I said, “We should take a shot at games.” Because I thought, “Here you have visual, you have technology,” and I knew that games had both components.

You could virtually transform a new media company into a game company. Happenstance, a French guy that we had hired, because of our relationship with our former CTO back in the good old days of RingZero, decided that he will take a crack at building a game presence. That takes us to 2008. So 2008, we got into games. We didn’t create games for the local market as the focus of the IT was largely local market. We focused almost entirely overseas. We created games for the overseas market.

We also did a little bit of work for hire, again, services business. But with the advent of mobile, we are able once again to leave console where we were a bit player into mobile, where we are … all of a sudden, we’re a publisher as well as a developer. We had a significant number of games, one of which was pretty good hit; My First Songs for children, about two million downloads and we still have it. Unfortunately, the platform that everybody was using; Apple and subsequently Google, had so many applications on them that it was very, very difficult to differentiate.

We have a new game company that was doing work for hire, taking in projects from overseas, mainly Europe, and we have an IT company. It is basically slowly going down, because we created our own competition, but some really big players were coming into Thailand. Mainly Indian players that had the sophistication and the experience to extend beyond their own borders and were looking for markets other than the United States in which they were already players.

By 2015, ’16 we decided that service is not such a great idea if you’re basically building, empowering managers and there aren’t the constraints that there are in the United States so we’re creating our own competition. So we decided to focus on product.

Genup: This is which year about?

Asmat: 2016…games were doing quite well, just chugging along, never really big. Once again, opportunity finds us because of our experience in mobile, we had an opportunity to do a gamified application for a large corporation. We had an opportunity to take over a game that was limping from an American company and slowly made our way into AA, AAA games, which is where we are right now. The evolution over eight years saw us go from console to mobile, make mobile more sponsored games where we would do game development as a service.

That sounds like we’re still in the services business, but we’re not. We basically run the games and continue to develop the games. Games itself started as hosting, web, new media, again games, mobile games, then mobile and console, which is where we are right now. We prefer to build a product, keep the product or build a product and manage the product for a client. IT was doing the same thing.

But that’s uneconomic if you don’t want people to come in to experiment, kill the company, and move on and do experiments elsewhere. You can’t build something, unless you have ClientZero. If you have ClientZero, you can go ahead and build it. You need ClientZero. Otherwise, you’re basically going to exhaust your capital.

If you are looking at startups, you’re either in a business that absolutely needs what you have. It already exists in the market. In other words, you’re replacing an existing product with something that is cheaper, better. Most good products are cheaper, better or dis-intermediate or create value. If you take a look at Uber, they created a company that intermediates between the owner of a vehicle and the person that just wants a taxi and they sold them something completely intangible and made money in the middle through intermediation.

Dis-intermediation is where you no longer need something that is the middleman. Usually in the finance industry, you dis-intermediate. And it adds greater value to both sides, you would think.

The other thing is transform the industry, make it easier. If you look at what Ticketmelon is doing, it did not start with them, but definitely they put their brand on it. They put a twist on it that the big guy couldn’t do in Asia and made it more user friendly to extract value from something. Startups need to have a market that is willing to pay you. In other words, you don’t have to negotiate price. Whatever price you offer them seems reasonable for what they’re getting in return. Let’s take for example in travel.

A travel agency, essentially people call up, “I need a booking.” You don’t want to go through OAG. You don’t want to do all that stuff. You’d like them to find a cheap flight from here to X, Y, Z. Then that was dis-intermediated. You no longer need a travel agency. Not only that. You not only don’t need a travel agency; you don’t need anybody to book a car for you or a hotel for you. It depends on how much inventory they are willing to take, and then all of a sudden travel agencies needed to specialize. One of the ones that we work with comes from a particular country to Thailand. They also have other destinations, but 400,000 from that particular country come to Thailand.

Genup: Which country is this?

Asmat: Russia. 400,000, at one time, this was a safe haven for Russia and for Russian money.

All of a sudden, you had a lot of Russians destined to Bangkok. So this agency catered to them. What you do is you don’t dis-intermediate the agency, they’re pretty smart, and say, “We extend the value of what is delivered to the tourist as hotel, transportation, and then what we introduced is rewarding them on the spot for favoring somebody that you have a partnership with. Whether it’s a restaurant, a boat company, something, brands that want to advertise. There are all kinds of ways to extend value.

You just need to think of the problem and work through it and have knowledge of the industry that you’re trying to penetrate.

Now we’re in products, and they’re less vulnerable to theft. Well, intellectual property in Thailand is not very well protected, but yet it’s harder, because your product is out in the world already. You can prove it easier. There are some big players in this market. The bigger the player, the more immune they feel. So, if you … forget the homegrown ones, let’s think about overseas players that come to play here. They’ll do exactly what they do in their own country. If you sue them, they’ll keep you entertained in court for the next two years until you run out of money. So you have to be really, really clever to do business in this market, understand the limitations of the law and apply a set of ethical standards that may be imported, but are improved upon here. What’s very good is the ability to transform is if you are perceptive and see where the market is going, you can continue to leverage the assets that you have to make it into something that has adapted to the current situation.

As I said, transformed five times and survived.

Genup: Is Ringzero self-funded or do you have VC money?

Asmat: it’s owned by two shareholders, my wife and myself. Never wanted to, and that is wrong. Also, it stops people from interfering in your business. A startup looks to the market for funding. This isn’t the best market for startups. From personal experience, I think you perceive Ticketmelon as a good startup. It is really unusual. Very, very unusual. Most of them basically are another hamburger.

Even those that are intelligent, developed overseas, sometimes never hit a critical mass. They need somebody special to come in to transform them. The basic idea is there. Take Food Panda… it took somebody to really move it, but somebody who had been in the startup business for a while.

Genup: How do you stay motivated?

Asmat: Fear. You stay motivated by not being in a business that is not interesting for you.

If you look at some entrepreneurs here, what keeps them motivated, they come from families that, all things considered, if they retire tomorrow, they’d have a place to live, have cashflow. They’d be okay. In a hierarchical society, how do you motivate a person that is by birth demotivated? We used to hire people that went to English speaking schools, so ISB, NIST, Bangkok Pattana, RIS, thinking the framework is sufficiently adapted that we can work with these people so they can understand the concepts that are largely important. A lot of the people early on that we tried to hire is, “I don’t need a job, I’m just in here for fun.” That’s a problem. How do you motivate a person like that? They need to be interested in succeeding.

If you look at Panupong for example, he wants to do what he did, and he wants to get to where he’s going. It doesn’t mean he’s not going to make mistakes, but he wants to. You absolutely need to want to.

What motivates me is making people better. Why would you want to do that? Makes you better in the process. If I wanted to make a small fortune, I wouldn’t have started out with a larger fortune and ended up where I am right now. The issue isn’t that. It isn’t all about money, but money is a benchmark.

It tells you if you’re being successful or not, but employee satisfaction also tells you if you’re being successful or not as well. Without people, you have no business.

Without clients, you have no business.

And with clients and good people in this market, how do you keep them? Because the way you grow in this market as a person that comes from a middle class family is you have to go from company, to company, to company, to company to increase scope, to change focus, to do things that you might otherwise be able to do in a company by moving from section to section. If you grew up in GE as a professional, you have moved around. If you belong to a smaller or even a larger company in Thailand, how do you grow when there’s no training and development?

People like us basically do a lot of the various jobs that are apportioned to other people. We do HR, training and development, by good fortune, finance and business development, understanding and working with people. My motivation always has been people. I’m a people person. I don’t care where they come from. I like working with them.

Genup: Who do you admire?

Asmat: It’s a moving target. I admire Steve Jobs, because of all the mistakes that he made and that he basically didn’t come from privilege. That is something that I absolutely admire, and that he was sufficiently aggressive, that when he walked into 3M into their development park is to recognize things that were the future. He wasn’t prescient. He’s just good at working with people and he loved product, good-looking appealing product.

He only made one big mistake, and his great good fortune was Sculley nearly killed the company and allowed him basically to come back.

So starting and finishing, Steve jobs. But how dumb do you have to be to take alternative medicine when you have pancreatic cancer?

Many people would admire a pragmatist like Bill Gates is … I am not a zero-sum guy. Zero-sum is typical of all data is I win, you lose. It doesn’t mean that you won’t have fun losing. Is when you go to the store, you buy something, you win. You get something and they win. You think that this is a win-win. It’s not. It’s actually they buy it cheaper; they sell it to you more expensively, and they happen to be in a place where they’re one of few outlets for that particular thing. It’s still pretty much trade, Mercantilism is pretty much zero-sum.

Non-zero-sum is quite literally win-win, is I give you your wildest fantasy and in so doing, achieve my wildest fantasy. Obviously, the two fantasies are not identical.

If you look at Uber is creating win-win, you own your car, you want to make a little extra money. I think technology allows you to create win-wins.

Genup: What don’t you like about being an entrepreneur? You come from Banking, which is a very corporate world.

Asmat: I actually look for people that come from large corporations, particularly if you subscribe to the belief that there are two kinds of people. Day people, night people has nothing to do with waking hours or preference for time of day. Day people are the majority. They are people that are regular. They like routine, they do routine. Then there are the people that are, to a large extent, ad hoc. These are deep thinkers, people that lose track of time, because they are ad hoc. They think of it today, they assign it a level of importance and then they move on to something else.

By the time they come back to that important thing, two, three months have elapsed and maybe an opportunity has gone. What a large corporation does for you is a business cannot be a practice. You can’t be a dentist and in business, because a dentist can only do this, you have 24 hours per day to ply your trade. If you hire another dentist to be a business, they won’t necessarily reproduce your product. Right? Excellent. So you go to a business. It’s no longer this, it is this times 50. I need to teach people how to do this, and to do it in a particular way. So businesses are inclined towards process.

They teach you that in order to be successful, you will need to do certain things in a regular way, so you don’t go running off reinventing the wheel every five minutes. If you come from a discipline, whether it is self-imposed or imposed by a corporation, you’re better off. For me, I understand, and I value process.

Now what I don’t like about being an entrepreneur is sometimes risk and sometimes legal and ethical interfere with you doing what is pragmatic. In other words, I like to believe I’ve always done the right thing and it’s not the best thing for business.

Doing the right thing and doing business sometimes conflict in a big way.

Genup: What would you tell your younger self?

Asmat: Create rules for yourself and make sure that after you’ve created the rules, that the business is still viable.

Genup: Rules for yourself or for your business?

Asmat: Rules for yourself first. If you’re going to start a business, the business reflects you in some respects. Like, how you treat other people. Again, we live in a hierarchical society. At the high end of the hierarchy is wealth, power, sometimes combined.

And how you’re going to deal with that in this particular context, particularly if you either come from wealth or power and choosing not to use it. I’ve lived in Thailand for a long time. I still think of myself as purely American, so I bring my context with me is frameworks are wherever you are. It’s the associations that you have, small and large. We live in a society, and there are certain hallmarks that define the society. Same thing with the United States, no matter what Trump says.

The framework that we bring is there’s no difference between you and I, ultimately. You might be better looking, but at the end of the day is we don’t focus too much on the minutiae. You focus on big picture. Corporations allow you to focus on big picture.

You also need to produce results. It’s tough coming from a different framework, because I assume things about you that might not be there. Worse, you assume things about me that might not be there either. Then the ultimate conversation is, this is the way business is done here. Then you have all kinds of repercussions.

You need rules. You need rules for yourself, and you need rules for the company. Startups are anti-rule. They’re turning statements on their heads incorrectly. Let’s take work-life balance. When a 23, 24-year-old walks into the office and says, “I’m really, really interested in work-life balance.” First of all, you know there is a parent. Second of all, you really have to check and try and understand, do they know what they’re talking about? If they do know what they’re talking about, don’t hire them. Because if at 23, 24 you are worried about work life balance, you’re not going to produce anything in the way of results that are significant.

Microsoft used to hire people straight out of school, and they were the most productive for the first three years. They were like bundles of production, energy. In the most productive years, you’re not thinking balance. You’re not thinking life. You’re not supposed to have one. You’re supposed to be seeing, “Is this the kind of industry that I want to work in?” Is okay to make mistakes, so that when you move, you move on to a better place that’s more suited for you.

So rules, yes, but make it seem pleasant. What creates powerful teams? If you ask people, the majority of people coming in, they’ll say, “A great workplace creates great teams.” If you go to Google, which is what they’re trying to emulate, they’ll tell you it’s the reverse is great teams make the great workplace. You absolutely need the raw material to create a good company.

You create a good company; people will flock to you.

It’s not the great workplace. It’s the great people that make the great workplace.

Part of what people bring are their own personal rules. Thou shall, thou shall not.

Genup: What does success in life mean to you?

Asmat: What does success in life mean to me? It’s different for everybody. I’ve always thought of myself as a professional, to create a professional success in addition to a familial success. It’s nothing that competes with family. Nothing. Obviously, you need to keep that in check, because if every time mother, father, brother has an inopportune moment and you leave your workplace, you are never ever going to be able to hold down a job. It is a balance, ultimately initially. You are creating a reputation for yourself, then extending that into your personal life, is you need to constantly grow.

Definition of success is constant growth, personally and professionally.

Related posts

Today's pick

Hot topics

Welcome to Generation Upstart

It starts with an idea — a fusion of thoughts and experiences, a blending of desires and dreams. Bursts of electricity fueled with faith, love and creativity leap across synapses generating the necessary expression to give it real form and substance. Sometimes, an entrepreneur’s call…

Careerlist: Never Waste a Crisis

According to Michael Scissons, the most important thing you can do to maximize your chance of entrepreneurial success is to build your tribe. Start as early as possible, trimming and pruning like a patient gardener, while continuing to add value to the network. For these…

RingZero: On Employee Satisfaction and Success

Great people make the great teams that make the great workplaces, and Mr. Asmat Yousri is a big believer in people. After all, he has been at this since 1996. An ex-banker, he saw no obstacles transitioning from a corporate position to an entrepreneur. In…