Genup: Please tell us a bit about yourself.

Michael: Yeah. So I originally grew up in Western Canada, which is, it’s a two day drive from Toronto, and a day and a half drive from Vancouver and you’re in the middle, and it’s very flat. And the joke was you could watch the dog run for three days, because it was so flat through the green fields.

I had an interesting upbringing that was a mix of unlimited freedom, let’s probably call it ADD, farming and business. My father was an industrial and organizational psychologist. My mother was a high school principal. So, had unlimited freedom to test and experiment with different business ideas. And I was lucky that I was in a city of 300,000 people because the ability to test and learn and fail and not go under was there. So I could try different ideas within my city. And it was small enough, enough so that I would see whether it worked or not, but it also wasn’t stupidly expensive to do anything.

So I had this really unique upbringing of experimentation and entrepreneurship and trying different businesses. I had an internet company in elementary school, and then I was a concert promoter, and was in virtual real estate tours. I had a yard work company when I was eight. So I really tried a bunch of different stuff.

I went to the University of Saskatchewan, which was my hometown school. I didn’t actually know that there were colleges in other towns, to be honest. I never had the idea that I wouldn’t go where I lived, …never entered my mind that one would think about going to a different school. So I went there and then my last day of college, I moved to Toronto and then started my adult working life from there.

Genup: So when did you start your first business? How old were you?

Michael: I think it depends on what you define as your first business. I remember being six years old, going door to door, trying to sell my training wheels off my bike because I saw that there was opportunity to make money. I sold them to an old lady that didn’t even own a bike. I think she’s thought that I was cute, and then I had a lemonade stand as I think a lot of people do when they are really young. And then I had a yard work company. Then I had an internet company then, I was a promoter. My first significant business started when I was 24. I started a company called Syncapse. We raised about two and a half million between the ages of 24 and 26. And then on my 26th birthday, we closed a 25 million series A. So that would’ve been my first like adult business.

Genup: So you never wanted to do the corporate life thing?

Michael: You know what, it was never really a deliberate decision. I think I’ve always naturally been geared towards the creativity and the freedom of running and doing your own thing. I have done the corporate life. When I was 19 or 20, 19, I was a sales supervisor at the local radio station, and was running our outdoor sales team. So, that was a year and a half, and I got to see what that was like. I joined AB InBev for a while as entrepreneur in residence, and then global head of e-commerce. So, I had a big team around the world. For me, corporate life isn’t the enemy, because I think the thing about being an entrepreneur is if you’re successful, there’s a very good chance that you’re going to have to have maturity to either, go back into corporate life or become corporate life. So, if you exit and you get bought by a company, you work there. And you’ve got to be there for a few years, at least. And you’ve got to navigate the system and work in a matrix and do all those things. If you go public, you are a corporate life, and you’ve got to manage that. So for me, the enemy has never been about corporate life. It’s been much more about trying to structure my life to have the creativity and the ability to create new things from scratch, which I like to do.

Genup: Talk to us about Careerlist. What is it about? What’s the core concept?

Michael: Careerlist started when I was working at AB InBev and we were needing to ramp up a team around the world, and I saw just how inefficient and slow the process was. Careerlist went through a few different iterations. So we originally started trying to build a tools company to build recruiting tools. We learned pretty quickly that we weren’t… That wasn’t going to be a market we were likely going to break through in, because there just wasn’t enough velocity or price point in that market for it to make sense. Where we settled on is really building a really intelligent network of insiders who were able to make referrals and recommendations. So Careerlist is basically a network that allows companies to use the platform and our services for their leadership recruiting. And instead of just having a recruiter that goes out and searches LinkedIn for you, we have a broad network of industry insiders, so we’re able to put out a note to, or text to, a very wide network of insiders. They make recommendations, and we’re able to make hires from personal referrals from people that have already been validated in our networks.

So the reality is that we get a lot more candidate information intelligence. We know a lot more about who’s in market and who isn’t. And we’re able to move much faster with a higher degree of trust because, … We’re really using people’s experiences and recommendations across a broad spectrum of the industry to make those recommendations, to help drive the hires for our customers. So we started a couple of years ago I think in this model, and we had, before COVID, we had had seven quarters of consecutive growth. We’ll have one quarter of non-consecutive growth now, and my hope is that things will come back. We’re already seeing really strong signals that Q3 and beyond look a lot better. So the focus right now is just on continuing that focus and cost management to come up the other side in a strong place.

Genup: So who then is your customer?

Michael: Our customer is the client, so it’s usually the hiring manager. Our network members are the talent.

And the interesting thing about the recruitment, talent business, especially when you’re in the leadership space is that your candidate, and your talent, and your customer are fundamentally the same person. So, I’ve got multiple examples where one month, we met a candidate through a job search the next month they were making referrals for their friends.

The next month they got a new job, not with us, but now they’re the customer. So the fun thing about the network is that you’re really maintaining a broad spectrum of relationships. But you’re able to help these people in a really holistic sense because, they themselves are people and ultimately have a lot of different needs. But they’re really the same person that, especially in the senior levels, the people looking for jobs, looking for teams; you’re a resource they can access to support themselves and support the companies they work with, holistically.

Genup: What were your initial hurdles when you started out?

Michael: The initial hurdles were kind of two fold. One, when we originally started we were trying to build a marketplace. And what we were trying to do was ramp up, not treat the network as a referral network, but treat the network as an open candidate pool that people can hire from. And our original hurdle was; the cost to build up that pool of people.

Looking at what you could sell, make money from a hire, compared to your decay rate. That didn’t work.

And if it did work, it only worked for tiny sections of the market. Maybe salespeople, maybe engineers, but even that. Because the challenge is if you grow that pool, you become bigger, bigger, bigger, bigger, bigger, your value proposition, knowing who’s in, it goes away. Because, basically at scale, you just become dead. So, that was a hurdle. So we had to rejig the network to make it more about using the collective knowledge of the network and basically treating it like every search you use the network, pop up a new marketplace. So, that was something that we had to learn and overcome.

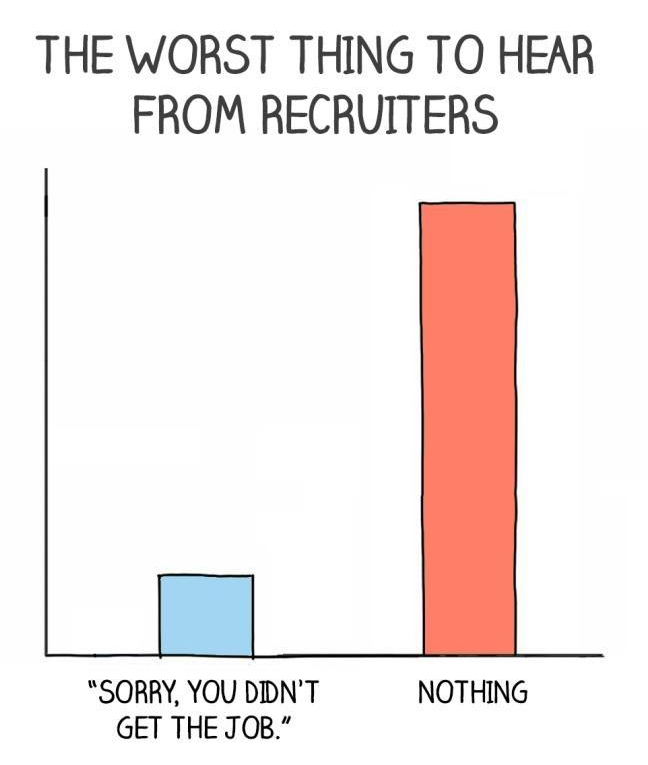

I think the second biggest thing was just learning how to sell, because the talent market was a market that was really hardened to sales. Where, if you think about, first of all, who’s your buyer; is it HR or is the hiring manager? We originally thought it was HR. Our response rates talking to HR was zero, no one responded.

Our response rates talking to hiring managers were better. Because, they had an empty seat, there was a bit of time. But the challenge was that these people were all incredibly hunted people. They were getting hundreds of emails a quarter from HR technology companies, trying to sell them HR technology.

They were getting tons of emails from recruiters who were trying to, “Hey, we’ve got a candidate. We can’t tell you who they are. We can’t tell you where they live, but they’d love to talk to you. Sign this contract and we’ll send them over.”

And they were getting chased by candidates as well, that are often unvetted. So, the market had really been predisposed to say, if you email someone about recruiting or talent; lights off. They’re not going to respond.

So developing our segmentation, and our approach, and how we think about lead generation was probably the second biggest challenge that we had to face.

Genup: Where do you see your business, say five years from now?

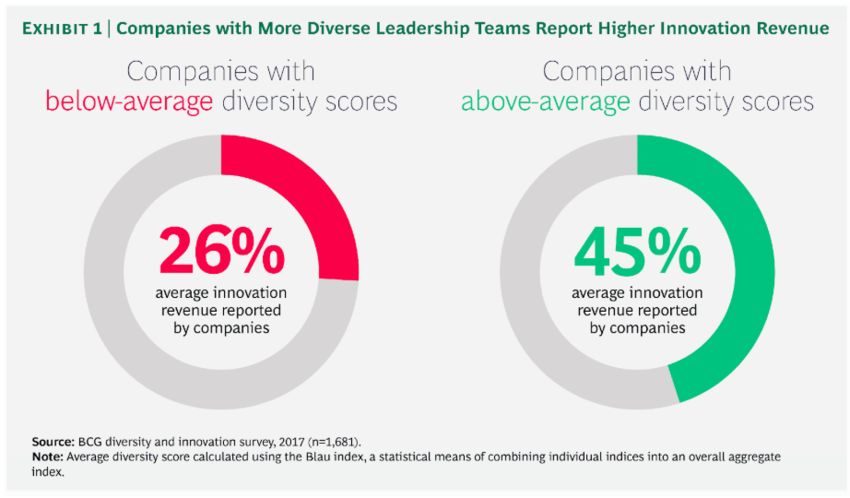

Michael:Thinking, five years, obviously I’m going to say bigger. Because, I think everyone would say that. But I think there’s really an opportunity to build the most connected talent company in the world. That knows everyone that has the most information, intelligence and can really be the most helpful to some of the top performing, most diverse talents in the world. I think that becomes, more important today than ever. Because, we’re seeing a lot of walls around locations, and geo locations, and things really being broken down where a company that would have said, “We’re only hiring engineers in New York. Everybody needs to be together.” They’re now like, “Maybe we should hire in Toronto. Maybe we should hire in North Carolina.” And then, “Okay, maybe we should look at Thailand.” And I think as we get bigger, the need of trust becomes more important than geolocation. So, we’re trying to really build that trusted network where you can get a broad array of talent and options quickly, from the areas of the world that you’re looking for when you want to build that team. And make bring everything to life pretty quickly.

Genup: Have you ever experienced a business failure?

Michael: Oh, God yes.

So, the first success that I talked about, raising $25 million on my 26th birthday; we ended up raising about $40 million. And that company went to zero. And we managed to “sell the assets”, It was a terrible outcome. Some of the entities filed for Chapter 11, some didn’t. It was a mess. It was an absolute crash of a failure. And we went from 300 employees to zero. From a substantial valuation to zero, in a very short period of time.

And I can make a lot of excuses for why that happened, but the reality is I was the youngest player in the book and I didn’t know the playbook, and I didn’t know how to focus on an exit, and I didn’t know about market timing. I didn’t know about all these things for what was a company that was built in a very transitional market. That market isn’t nearly as hot today, 10 years later, as it was then. And didn’t end up becoming a big, long term, viable, software market.

So, we went to zero and I was 29 at that point. I remember being up on my rooftop, drinking many bottles of rosés the end of the night, after the crash. Trying to figure out how to do it. But the reality is that for some reason, a month or two later we launched the second company.

And I was too tired to be CEO at that point. And I had an amazing partner, Grant, who would work with me in my first company, that took it and ran it, was the co-founder and the CEO of it. Coming from that failure, literally two weeks later, we launched the next business that went on to become a crazy success. Especially in that industry, it was the most successful Exit and Financial Return and impacted 80% of the Fortune 500 companies who used that solution for what we did within two years.

But that company was born from the depths of darkness, of a pretty dark crash, that for some reason, that seemed like a great time to start a new business. Even here. And then I always say never waste a crisis because that’s I think when your best ideas come, I see a lot of eager MBA grads, not to call out the MBA grads, but they were like, we’re looking for a startup idea. We’re looking for one. Well, good luck. Let me know when you find one, because I think our best ideas are really born out of pain. So even in this darkness when you have COVID when Careerlist was challenged for a quarter, and now come back, I have launched and funded two new companies that will be out that were based on the new reality of the world.

I’ve always found you focus on those pivotal points of either your life or those pivotal points of the market where everything changes or goes dark. Those are the moments when you got to run into the house that’s on fire when everyone else is running out, because those are going to be when you’re going to find the best insights, ultimately have the best likelihood of a successful outcome. Because if you start at the bottom, you know you got the whole build back up to become successful. If you create a company a year or two from the crash, Careerlist is a good example, you got to go back down, and you got to come back up. It’s much easier to start here, and every market has its own cycle but… I think in these inflection darkness periods are the best times, is where you find your new big ideas.

Genup: Do you have a process of how to come up with these ideas? Because at the darkest times most people are just paralyzed with fear.

Michael: My process has always been pretty simple. So when I was a kid, I had so many ideas that it was unmanageable. And I would think about a new business and probably design a new business card every month. Hey, I’m doing this, hey, I’m doing this, hey, I’m doing this. And I didn’t put enough time in as a 16, 17-year-old to see… I saw some of them do really well, I paid for college and all those things with them, but I was really, I was beyond the line of experimentation into having attention deficit disorder.

I think my hardest lesson was really learning to learn… The hard lesson taught me that when you’re in something you’re in it for a long time. So you have to be incredibly diligent about what you go into, that you’re going to be interested enough, the market’s big enough, it’s interesting enough because when you put your name on it, you’re there and you could be there for three years. Very unlikely. You’re probably there for seven or 10 years at least. And some people want to find something they’re in forever and that’s okay. They want a cashflow business and that’s great. But for me, I know that it’s at least a five to 10-year horizon when I go into these things, whatever capacity that looks like. So what I found that it’s actually done is that fear has actually kills most of my ideas now, where I don’t really get as many anymore, because I don’t want to launch that much stuff. Success is if I can launch five companies in 10 years. That’s awesome. That’s enough, I’m good. Someone I really aspire to, a guy named Kevin Ryan who built MongoDB, Business Insider, Gilt Group, Super Coffee, a bunch of really diverse brands, diverse markets. And up until recently, hasn’t had a substantial team focusing on the core.

But my process is really driven by my interests and via my market. And it’s really driven by my exposure. So the only thing that I do when these things happen, when I’m looking for something, it’s really simple. I talk to more people and I say, hey, what are your problems? Well, my problem is this, my problem is this, my problem is this. And if I start to hear the same problem from multiple people, okay, that’s interesting, and then I’ll look into it, but my wife always jokes say, you’re always on the phone. You’re never not talking. And it’s just sometimes she’s like, well, why won’t you talk when you’re off the phone? But different story. I’m working on that.

But my process is really built off of having a broad network and having a lot of conversations and understanding and listening to people’s pain points and having a network of which I can rapidly validate ideas and solutions. And I find for me having that, having really invested in that network over the last 10 years.

That’s the most important thing is maintaining those relationships, whether it’s investors, or validators, or idea generators to get a wide enough spectrum of opinions. And that’s really how my process runs.

Genup: How do you stay motivated? Any tips?

Michael: So it’s very much ingrained within me. My late father would call me every morning at 5:00 AM for probably 10 years and say, are you up, are you being productive? Let’s get going. This is the best part of the day. Other people are at work and you’re not, you got to get going.

And so I very much grew up with a farming mentality of you get up when the sun gets up, you go out, you work, you go to bed when the sun goes down. I’ve had to balance that to make sure that I’m spending time with my kids and enjoying life a bit more than probably the extreme case of what I would have forecast a while ago. But the motivation, I think for a lot of people is that they’re driven by interest in something bigger than themselves, or fear of failure. And I think for me, it probably sits somewhere in between the two of interests of… I genuinely love building, creating new things. And I’m genuinely afraid of failing or something going wrong somewhere between that interest and that fear every morning, waking up with a sense of urgency around the things I need to get done.

Genup: Who do you admire?

Michael: Yeah. I admire… And I think it’s evolved. I think I used to, when I was 20s, I used to think it was about the money and I’m ashamed of this now, but I remember reading The Art of the Deal. I remember when The Apprentice came out and I was hanging out with Bill Rancic, who was the winner of the first Apprentice and some friends who were up in his hotel having drinks, the Glengarry, Glen Ross, Wolf of Wall Street, whatever period I think promoted some really unhealthy beliefs. I think it permitted some really unhealthy behavior, especially when you’re an impressionable 20 something, early twenties. And I didn’t have the other exposure points that would have balanced that out. But I think the entrepreneur that I like the most has probably, historically, been Richard Branson. I always looked up to Richard Branson because he was in a lot of different industries and business. He treated people generally really well. I’m sure he has some issues and some things that will at some point emerge in the media, but he was always advocating for good and always interested in a broad array of business ideas and challenges and is genuinely a really nice person. I mentioned Kevin Ryan before, to me, he’s probably one of the most successful founders of our time and which no one knows who he is or his name outside the business, because you know all of his companies, but you don’t know him per se. That’s by design, I’m sure at some degree. But he’s built incredibly successful businesses.

I’d also probably say my wife, she’s probably the smartest… It’s been many years; I’ve still never won an argument and it’s not because I give up it’s because she’s always right and she’s researched it. She’s read it and she’s studied it. She’s infinitely smarter than me. Especially when it comes to thinking about policies or trends and things like that and learn from that. I think what I’ve probably done from then until now is the people that I look up to are a more well-rounded bucket of thoughts and ideas versus a very monolithic monetary group.

Because I find the idea that you achieve your goal of monetary success, which I was fortunate to do, you realize that really doesn’t mean anything and you might feel better for a month. I did it! And then it’s, shit. If you were unhappy, you’re back to being unhappy. If you’re happy, you’re back to happy.

Genup: You go back to set point.

Michael: You go back to set point. So then when you realize that there’s no big, massive change at that point, you start to realize that you’ve got to change dramatically what things look like.

Genup: What don’t you like about being an entrepreneur?

Michael: I don’t think that there’s anything I don’t like about it. I probably really enjoy the least is large-scale team management. I do better having one person who leads the day-to-day of the business to a large extent and manages the team and people of it. One, I’m a better manager and better leader I think, when there’s someone between me and them. It’s just the way that my brain works. Having a consistent filter and manager that can manage up and down as intermediary, I’ve found to become for me to be really important and have the best leverage on the businesses for myself, but also just for investors and everybody else because there’s some people that are just amazing at that.

I’m really good at maintaining relationships with people. No problem. Dinners, meetings, town halls, great. One-on-ones every week, no. I’m just not. I really tried and I don’t want them occurring in my schedule. And that’s okay. I’ve got to realize that I’m able to staff my life in a way that allows that to not be required for things to be successful. As long as you have senior people, a person that you partner that’s managing that, you can be the more visionary, creative, crazy partner, and you can have your executionary partner. And that’s fine, and that works. I’ve done that. I’ve had to learn finance from the ground up. I remember being 26 and going to these investment bankers talking about liquidation preferences and warrants.

I have a degree in sociology and drama. I don’t know what these people are talking about, but I’m just nodding, writing these words down, going in Google, okay. Now, I argue, I probably know more than most MBAs in terms of financial theory, international insolvency law, international immigration law, multi-jurisdictional transfer pricing because I’ve gone through it all. But I learned by doing that. That wasn’t a natural set point for me. I had to learn those skills. Some of those skills I never want to use again, International insolvency law, bad. I never want to do that again. But you’d be amazed at how many calls I get from people who are going, “Hey, we’re here, we’re here. How do we think about this? How do we structure it? What happens? How do you do the board?” And I’m like, “Okay, here’s the playbook,” which isn’t a playbook that I ever wanted to know.

But so, I think I’ve had to learn those things. I’ve had to set the systems up. And I wouldn’t say that I don’t enjoy those areas of entrepreneurship, but I… My grade three teacher said I’d be successful in life, if I had a really good assistant. She said that in grade three, she’s like, “Michael is really smart. He’ll do well if he has a good assistant.”

I have forced myself to get organized. And what I realized is that she probably was right, I needed help, but I didn’t have a really good partner. And you’d need to have a really good CFO, and then I’m fine. But that’s one of the things to me that’s really appealing about entrepreneurship is that you’re able to set your life up in a way that supports your strengths and your weaknesses. Where when you go and when I was working at a great… I was working InBev. Great company love it. Right. But at the end of the day, I was here, I was global VP. There were other global VPs. And as being a global VP, you’re expected to go to the same meetings that all the other global VPs go to. Go to the global leadership conference. You’re expected to sit in your annual planning meetings for weeks on end, going through the minutiae details of those things because that’s what a global VP does. You’re expected to manage a broad team and have one on one meetings in various ways shapes or forms. You’re expected to spend weeks going through performance reviews.

Everything I’ve just described, doesn’t lead up to my skillset, right? What leads up to my skillset is being able to define the path strategy forward, define portfolio strategy, make it happen, and have my number two go to all those meetings. So one of the challenges that I found with corporate life, was that you’re expected to behave the same way that everybody else does, and have the same skills everybody else does.

I mean, talk about diversity of skills and thought, you have to have diversity of organization of how it’s structured too, because, I’m really good at creating new stuff, but I’m really not good at going to the many functions because, that would be a large percentage of my life. So for me, I think it’s finding the ability to create my own structure. It was probably ultimately what I was really looking for. That I needed to find that environment that I could support my weaknesses and not just survive, but thrive, knowing what I’m not good at.

Genup: What does success in life mean to you?

Michael: I think that that answer has changed. In my twenties, I would have embarrassingly said, even up to 29, I would have said “Success for me is being able to do what I want, where I want, with who I want.” The reality is one, that’s an incredibly selfish worldview, and two, that’s a worldview that will inherently lead to unhappiness, with you and what you’re thinking about. Because your happiness either comes in building something or giving back and having a broader support for others, whether that’s your family, your coworkers, just random people in the community, etc.

I think in the era of the next 10 years, happiness is being able to spend time with the girls and watch them grow up, and my wife and my family. Build interesting and exciting things that end up becoming great places to work and becoming really successful in their respective fields. That’s ultimately what I think is going to become successful and happy in that era.

I think the success in the next era, it would probably come from having made enough money doing that, were able to really deploy capital in a way that has a broader social impact or a broader societal impact or work on just projects that are merely interesting. But I think that I’ve found that happiness is really a balance of a bunch of different buckets, and what those buckets are is going to evolve. So, like I had a bucket in my pre kid life era, and if I took those same buckets with me into my kid era, I wouldn’t see my kids often, or probably wouldn’t stay married very long. So I had to rejig with those buckets. But, as the girls go into high school and college, in 10 years, what happiness will look like, we’ll probably be like “Can I fly out to wherever you are going to school, come for dinner, please, please this year.” Plus building different and interesting things. But for me, the interest has always been in business.

Even now, we’ve got an ed tech company coming out, we’ve got a consumer products goods company that we’re coming out with, got Careerlist, that each person kind of has a strong leader in each of them. Happiness doesn’t come from solving one problem. For me, it’s the general interest of our business, family life, societal life. And then I’m constantly able to move with those buckets and within them.

Genup: What advice would you give someone who’s considering becoming an entrepreneur?

Michael: It’s a good question. I think what I’ve seen relatively consistently across a lot of different investments in people at this phase, is that your roadmap for getting one, your roadmap for being an entrepreneur is never the same thing. Everybody has their own path, but I think the most important thing that you can do is really work to build your tribe so that as you go into entrepreneurship, you have built a tribe and learned from a tribe or a school of thought.

And I probably undervalued this in my first job after school. Because my first job actually was working at a company that was super lucky, that ended up getting the rights for Facebook, and I ended up running Facebook sales in Canada and I was 22. You couldn’t have planned that. That was sheer luck. But what happened in that, there was an involuntary reaction was my tribe built up incredibly quickly. So I had a platform to build a lot of really good client relationships because I could call and everybody would answer Facebook. I met a lot of the early Facebook team, which became the future investors of the world, which then became connected to everybody else.

And I built a tribe there, and I built other tribes over time that have come together. But I think it’s really hard to not learn from a tribe, become part of a tribe that really mirrors a type of tribe that you would want to build yourself. So, getting a job min a smaller company, that has a leader, that you’re very close to the top, that you can learn from, that you’re exposed to the tribe, you’re exposed to who she or he knows, that you’ve exposed the problems, that you’re able to learn. And you’re really learning with somebody else’s money, under somebody else’s leadership, I think is incredibly important, and maximizes your chances of success.

If you go from all corporate life, and then 25 years later try to start something, that’s going to be tougher, to a large extent. Not tougher because you’re not smart. It’s going to be tougher because your overhead is going to require a lot of cash, because you’ve been living a good lifestyle for a long time. The tribe that you built are going to be less likely to be the people that you want to work with you, and even if they do come over, they’re going to be people that require more cash, because they’ve also worked at big companies, and use cash, so the likelihood that you’re going to have two or three founders in your life that will join up with you to start something is going to be harder.

The skills that you’ve learned, and the management principles that you learned, about the scale and process, and growing from big to bigger, and refining systems, and long-term management cycles, they’re not going to be like, “Let’s get shit done today. What are we going to do today?” So I think the most important thing you can do, and it’s never too late to do this, is just to make sure that you spend some time working from learning from a tribe of people who have the operating system that you’re going to need to be successful, and you’ll learn that for a couple of years.

I think you’re collecting your tribe, and this is a collection of people that you collect over life. I literally have an Excel doc that are just names, that I call the vault. The vault are people who, relationship-wise, you want to maintain relationships with, because they add value to your life, you add value to their lives. You work well together. You share a similar mentality. And that’s a growing list. It’s also a declining list sometimes. I’ve got people that I maybe added 10 years ago that I think, in terms of value set, we don’t align anymore. What they’re promoting in life and what I promote aren’t the same.

Delete row. And that’s okay. But I think when you’ve gone and seen a lot of these companies that have been successful, they’ve really been built by founders that came from a tribe. They came from a way of thinking, or a way that they learn.

But your hardest thing you’re going to do in your life is find those people that you’re going to work well with, because the failure rate and your wrongness rate is so high, that if you find that crew … until you’ve found that group, it’s going to be really hard. If you’ve had some successful outcomes with everything you’ve tried, you can probably start something by yourself. If you haven’t had successful outcome, and you’re doing it for the first time, you’re figuring it out, you probably need a couple founders with you, just dramatically reduce your chances of failure.

Those would be my biggest piece of advice. Find your tribe, collect your tribe over time, and be places that you can really learn the skills. Don’t focus on career. Don’t focus on resume building. Just focus on learning the skills that you need, and from a lot of people, I’m always like, “What sort of company … ” Like, “Have you been in sales yet?” “No, I never been in sales.” I’m like, “Get into sales for a bit.” Even if you get a job selling phone book advertising, or selling whatever, it doesn’t matter. Just sell something, because you’re going to have to sell to employees or people.

The more phone calls you can make every day and learn to sell, the better.

Yeah. Those have been my big learnings.

Genup: Wonderful. Hey, thank you so much, Michael.

Michael: No problem. Hopefully, it was helpful.

Related posts

Today's pick

Hot topics

Welcome to Generation Upstart

It starts with an idea — a fusion of thoughts and experiences, a blending of desires and dreams. Bursts of electricity fueled with faith, love and creativity leap across synapses generating the necessary expression to give it real form and substance. Sometimes, an entrepreneur’s call…

Careerlist: Never Waste a Crisis

According to Michael Scissons, the most important thing you can do to maximize your chance of entrepreneurial success is to build your tribe. Start as early as possible, trimming and pruning like a patient gardener, while continuing to add value to the network. For these…

RingZero: On Employee Satisfaction and Success

Great people make the great teams that make the great workplaces, and Mr. Asmat Yousri is a big believer in people. After all, he has been at this since 1996. An ex-banker, he saw no obstacles transitioning from a corporate position to an entrepreneur. In…